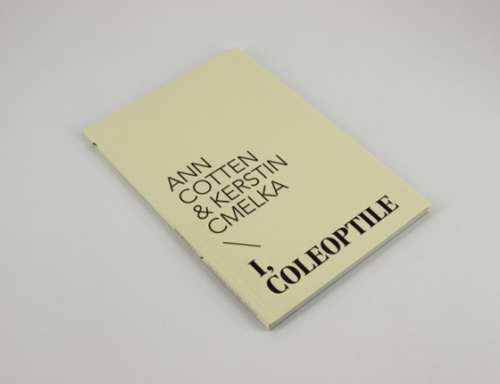

I, Coleoptile - Ann Cotten & Kerstin Cmelka

I, Coleoptile

Ann Cotten & Kerstin Cmelka

2010 English

127 x 184 mm,

88 pages, 25 b/w photos 2 ill., softcover with French Flaps

ISBN:978-3-00-032627-1

€12

Ann Cotten has published numerous work including Fremdwörterbuchsonette(Suhrkamp) which won in the Reinhard-Priessnitz-Preis. She also published a book on concrete poetry Nach der Welt: Die Listen der Konkreten Poesie und ihre Folgen (Klever Verlag) in 2008. The same year saw her receive the George-Saiko-Reisestipendium and the Clemens Brentano Förderpreis für Literatur der Stadt Heidelberg. Her latest book came out in August from Suhrkamp and is called Florida-Räume. I, Coleoptile is her first full length book of work in English.

Kerstin Cmelka is a visual artist and was born in 1974 in Mödling, Austria. Most recently she has taken part in Cold Society at KW69, Berlin, Gestures - Performance and Sound Art at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Roskilde, Denmark (2010), Scorpio's Garden in the Temporäre Kunsthalle Berlin (2010) and Playing Homage, Contamporary Art Gallery, Vancouver (2009). She curated Stolen from my subconscious, KW-Berlin, 03.03.2011 - 03.04.2011

I, Coleoptile is a repetition, but also a public rehearsal for a performance, yet to be seen.

— Lars Gustaf Andersson in Reconstruction 11.1, April 2011

Ann Cotten's poems are among the greatest to be written in German poetry today

— Jochen Jung in Die Zeit, Oct 2010

In I, Coleoptile Ann Cotten (b.1982, Iowa, USA) moves the ironic play with authorship and formal experiments of previous projects to the background and opts for a more intimate approach. At the suggestion of publisher Broken Dimanche Press she has written her first comprehensive collection of poems in English for which she has also collaborated with the Austrian artist Kerstin Cmelka. The end result is a beautifully crafted book in which poems on the theme of ‘emergence’ are alternated with black and white photos that evoke scenes from the infamous 1918 Vladimir Mayakovsky film The Young Lady and the Hooligan.

— Jan Pollet in De Reactor, Amsterdam

from DE MYSTIEK VAN DE SNIJBOON

By JAN POLLET

(www.dereactor.org)

Translation Jeroen Nieuwland

…

In this project Ann Cotten (1982) moves the ironic play with authorship and formal experiments of previous projects to the background and opts for a more intimate approach. At the suggestion of publisher Broken Dimanche Press she has written her first comprehensive collection of poems in English for which she also collaborated with the Austrian artist Kerstin Cmelka (1974). The end result is a beautifully crafted book in which poems on the theme of ‘emergence’ are alternated with black and white photos that evoke scenes from the popular 1918 Soviet film The Lady and the Hooligan. The poet Vladimir Mayakovsky wrote the script for this film, directed it and played the main role. In the photo series Cmelka portrayed Cotten as the male figure - the hooligan (character) annex Mayakovsky (actor) - who in the end is beaten up. This seems to suggest an identification with the Russian poet, rebel and communist. In the poems Cotten only once refers explicitly to Mayakovsky, notably in the last poem ‘Take away Kasbek’. ‘If this / mountainous / holy heap / is in the way, / then tear it down’, she says resolutely about Kasbek, the third highest peak in the Caucasus in Georgia, also Mayakovsky’s birthplace. Kasbek here is symbolic of everything that obstructs our view and because ‘our way is mistier than mist’ it is important to eliminate any obstacle. The final verses of this poem express an intense desire for clear (spiritual) vistas where the green mist, which hangs over the book, has finally cleared away.

But now what to make of that misty word ‘coleoptile’ from the title? It is a term from botany and denotes the membranous sheath of grassy plants, which encloses the plant shoot. It is the membrane that protects the germinating seed in the ground until it is strong enough to develop into a full plant. It is, therefore, an enclosing form fully at the service of an emerging organism. Or to paraphrase: I Coleoptile am only the provisional shell of a flawless bean becoming. It is tempting to see in this a metaphor for the ephemeral body versus the eternal soul.

On the blurb Cotten presents the book as a study on the ‘green bean’ whose form ‘is not public or private, neither phallic nor vaginal; if anything, it resembles the vague idea of a soul or astral body [...]’. A platonic interpretation offers itself: if the flawless, green bean is a model for the soul, the coleoptile is the symbol of the protective, but also restrictive body. Cotten opens the collection with a short piece of fierce prose: ‘The fucking green steam is full. A large depression has spread from one end of the sky to the other. […] All this ‘coming up to say hello’, fuckin plants, bad green, bad idea. [...]’

After this the word is given to the green bean’s budding seed. It feels confined and laments the tight fitting coleoptile, ‘I’m yearning and striving and goofing around, I am posing and feeling, but my feeling doesn’t go anywhere.’ Nonetheless, Enzo (that is the name of the budding seed) is addressed encouragingly:

O Enzo

thou sprout

coat of ow

out of coat

out of that

now.

We follow the genesis and the painful labouring of Enzo up to and including his disappearance: ‘Enzo tries, dries, dies. A variety of poetic forms reflects on themes such as ‘travel’, ‘displacement’ and ‘desire for understanding’. Regarding the latter coleoptile is also a cause of the unknowability of life. It then functions as an impermeable membrane between consciousness and reality, and could be a symbol for the inadequate understanding with which every person is condemned. In other words: In the brave efforts of the seedling we recognize our own attempts to achieve clarity and lucidity. And yet from all of these texts speaks the desire to remove all that hinders understanding, even the Caucasian Mount Kazbek. Occasionally Cotten gives the impression that the development from seed to mature plant is only a first stage towards a higher understanding, which could indicate a (tentative) venturing into mystical paths. Moreover, the notion of seeing in the smallest (a seed) a reflection of the cosmic, recalls a common tenet of mysticism.

But Cotten wouldn’t be Cotten if she would allow herself to be pinned down to a single mystical longing. There is no escaping the human condition as is clearly stated on the back cover: ‘If the circumstances require it, the American Socialist will show a sense of humour; and he will continue to do so until someone has figured out how people can live without food, love and shelter. InI, Coleoptile Cotten plays multiple registers at once: from philosophical-symbolic and mystical, to the contemporary reality of the Internet and pop songs. No genuine human feeling is passed over in the process. This simple love poem, for instance, is one to be reckoned with. Gone is the ironic playing about, gone the cerebral, hermetic Cotten. Full of spontaneous surrender she addresses the beloved in the most simple and direct words that could have come from a pop song.

Love me, love me, run your fingers

from my head all the way down

to where I stand on the ground.

Ask me, ask where I will go

cascade of ideas and lust

do I have the guts to know

what will lie apart and what is just a blow?

Find me, find me, as your playing

ceases to be all, by chance

upon a racing corner,

comet, glance.

Hidden in the inside of the folded back cover is the last poem, aptly named ‘Last’, in which the poet confesses that she has retreated into the cocoon of language. Language as the last protective membrane until her death.

‘Last’

No longer do I pass the intentions by but

I miss the rest. I am a woman as yet

in a cocoon. I am embarrassed

that one has caught me as I unfold

my first wing, still in the “real,-”bag.

Your hairy arms

o how I could swarm, admire!

How I could roll my segments

thunder-clean, I was stark cushions

with enough feet for all the world.

But he who touches me now gets splinters

and I go through the alphabet

in order to conclude, until my death.

Now please feed my pelt with poems

and with time. So much time, so many times a single beer.

I hear your voices. I am here.

With this lonely endpoint Cotton concludes a mysterious cycle of passion. Or so it seems: as an afterthought there follows a joke for adults:

What does a sun do when it sees a shiny blade of grass?

– Make hay.